In this blog, Professor Richard Kneller, Dr Cher Li and Dr Anwar Adem share insights from their PrOPEL Hub funded research project work on how to support businesses to improve performance and productivity through better management of digital technology.

The economic uncertainty and technological complexity faced by businesses was on the rise before the COVID-19 pandemic, but both have accelerated further during this difficult time. Digital adoption has been deepening across the entire spectrum of business life in recent years and data-driven decision making has become part and parcel of high-performance businesses. The pandemic has necessitated a further rapid digital transformation, workforce reskilling and new forms of organisational innovation.

The adoption of new digital technologies is often costly for various reasons. And this is certainly not the be-all and end-all since companies must also put in place appropriate management practices to harness their benefits.

According to software company SAP, using data as an example, less than 1% of data in businesses is analysed and turned into benefits. Or, as Marc Benioff – Founder and Co-CEO of Salesforce – once put, “every digital transformation is going to begin and end with the customer, and I can see that in the minds of every CEO I talk to.”

Arguably, the speed at which business now must react, and the costs associated in not doing so, are what has profoundly changed in this wired world – businesses now have little time to reflect upon the reactions from customers to this digitally enhanced experience.

Against this backdrop, in this project funded by the ESRC through the PrOPEL Hub, we explored the key differences to better managing digital assets by businesses. To do so we focused on a digital technology that plays such a pivotal role in a company’s interaction with its customers – its website, which is often powered by scores of software applications. A business website is the window to a company’s “soul”, acting as the second, or increasingly, the only, shopfront it presents to customers. Yet, the way in which companies use this critical resource is subject to a multitude of interpretations.

If companies use these web technologies inefficiently, this reduces the customer experience and lowers the benefits realised from their adoption. There are various reasons why this is the case, although information barriers about how best to use the technology and managerial inattention are often cited as the most important.

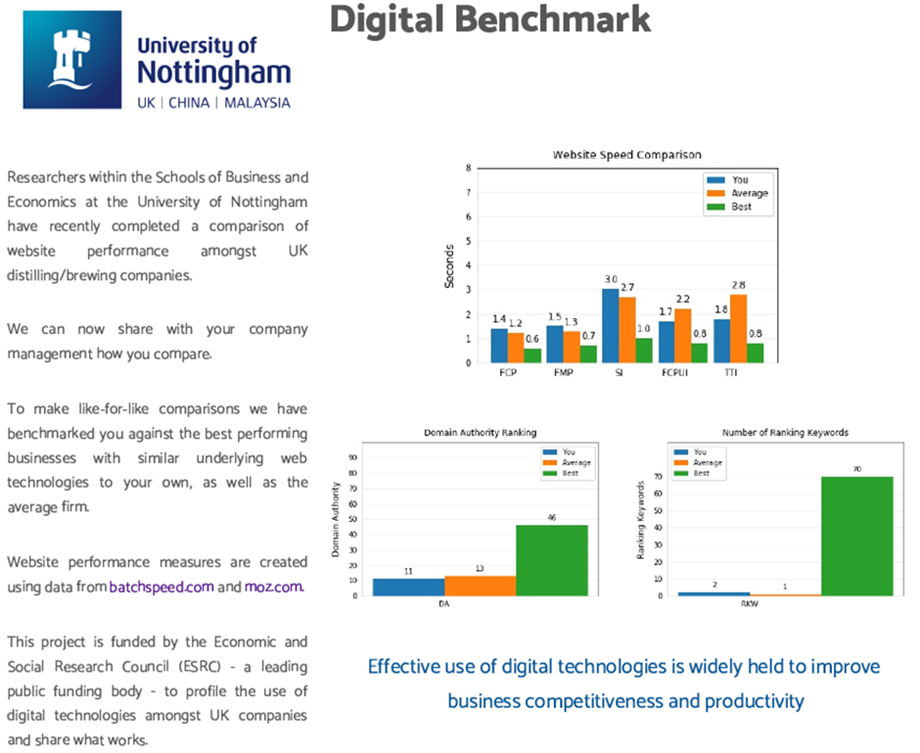

In this project, to generate improvement in digital performance, we designed a field experiment involving over 800 firms from a single UK industry – the distilling and brewing companies. Our treatment was designed to be minimally invasive, delivered in the form of a bespoke Digital Benchmark Report tailored to each company. It contained information on its website performance, which was benchmarked against the average and best performance amongst their industry peers. It also informed companies of the key components of a website performance management system and the need to utilise digital technologies more effectively. Where this was information that the business already had, then our information provided a nudge to re-focus their attention and potentially improve the experience of customers using their website.

Half of all these firms were randomly selected to receive our business support treatment (see image) and the other half were simply monitored as a control group, allowing us to quantify how important this information or the reminder was.

Our benchmarking exercise focused on a comparison across seven website performance metrics that are often used by web developers and considered to influence customer experience and ultimately conversions into sales. Five metrics measured the loading time of a website on a digital device and two additional metrics measured search engine optimisation (SEO) which affects the website’s Google ranking.

We identified gaps in the baseline performance data across firms that were substantial. The best performing websites loaded some three to six times faster than the worst and contained 38 times the number of keywords picked up by a search engine such as Google. Clearly, there was much that businesses with under-performing could do to improve. Throughout the trial, our main objective was to observe any behavioural changes amongst businesses in response to the information given to them about how efficiently they had been using technology and their relative ranking.

In a nutshell, we found causal evidence indicating that the information we sent to business was important, helping to generate improved website performance amongst UK companies. This improvement occurred for aspects of performance that are difficult to analyse without sound monitoring processes. Improvements happened quickly, within a month or so, with further positive changes at three months and six months. Since the effect of the information depended on the performance metrics being measured, it was deemed consistent with the absence of a good performance management process for digital technologies among UK companies in general.

How much of this is due to a lack of knowledge about what good performance management processes might include, and how much is simply due to managers not paying sufficient attention, is important, as they suggest different policy responses. If it is about knowledge, then this would suggest management training could play a key role. If it is about inattention, then a periodic reminder might well suffice. Our ensuing analysis suggests that both factors were present. We found evidence that some businesses undertook action, such as the use of web performance-monitoring and/or analytics software that was consistent with the use of better management processes, whereas others told us in a follow-up survey that we served a prompt for them to act.

Overall, our project illustrates why it is important for businesses to look beyond the adoption of digital technologies to find their digital “souls” and manage them better to unlock such businesses benefits. Positive change will require significant experimentation and learning by managers. But it also affords a new opportunity to build more robust internal systems for managing digital assets by reflecting on best managerial practices for enabling these transitions. In our ongoing work, we will continue to explore what sort of information feedback is most effective in nudging companies to improve, and whether companies already collecting performance data respond differently to future interventions vis-à-vis those not capable of self-monitoring.

For additional information, the project team can be reached at: Cher.Li@nottingham.ac.uk